Preamble

The publication of the 12th issue of this newsletter in November last year, coincided with the Chinese Nobel Laureate in Physics Professor YANG Chen-Ning’s 100th birthday. To celebrate this important occasion, The Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) held a large-scale special exhibition as part of the celebratory activities. For that edition, we also published an article titled "A Century of Physics - A Public Lecture in Honour of Professor Yang Chen-Ning at One Hundred", written by Professor Kenneth YOUNG of the Department of Physics, CUHK, not only to introduce Professor YANG’s outstanding academic achievements, but also recount the close relationship he has established with Hong Kong over the years.

In fact, although Hong Kong is geographically small, it is a place where some Nobel Laureates in Physics resided and were educated when they were young!

In this issue, we are going to introduce another Nobel Laureate in Physics - Professor Charles KAO, who is known as the "Father of Fibre Optics", about his great achievement in engineering and physics as well as his remarkable contribution to the development of higher education in Hong Kong.

Father of Fibre Optics

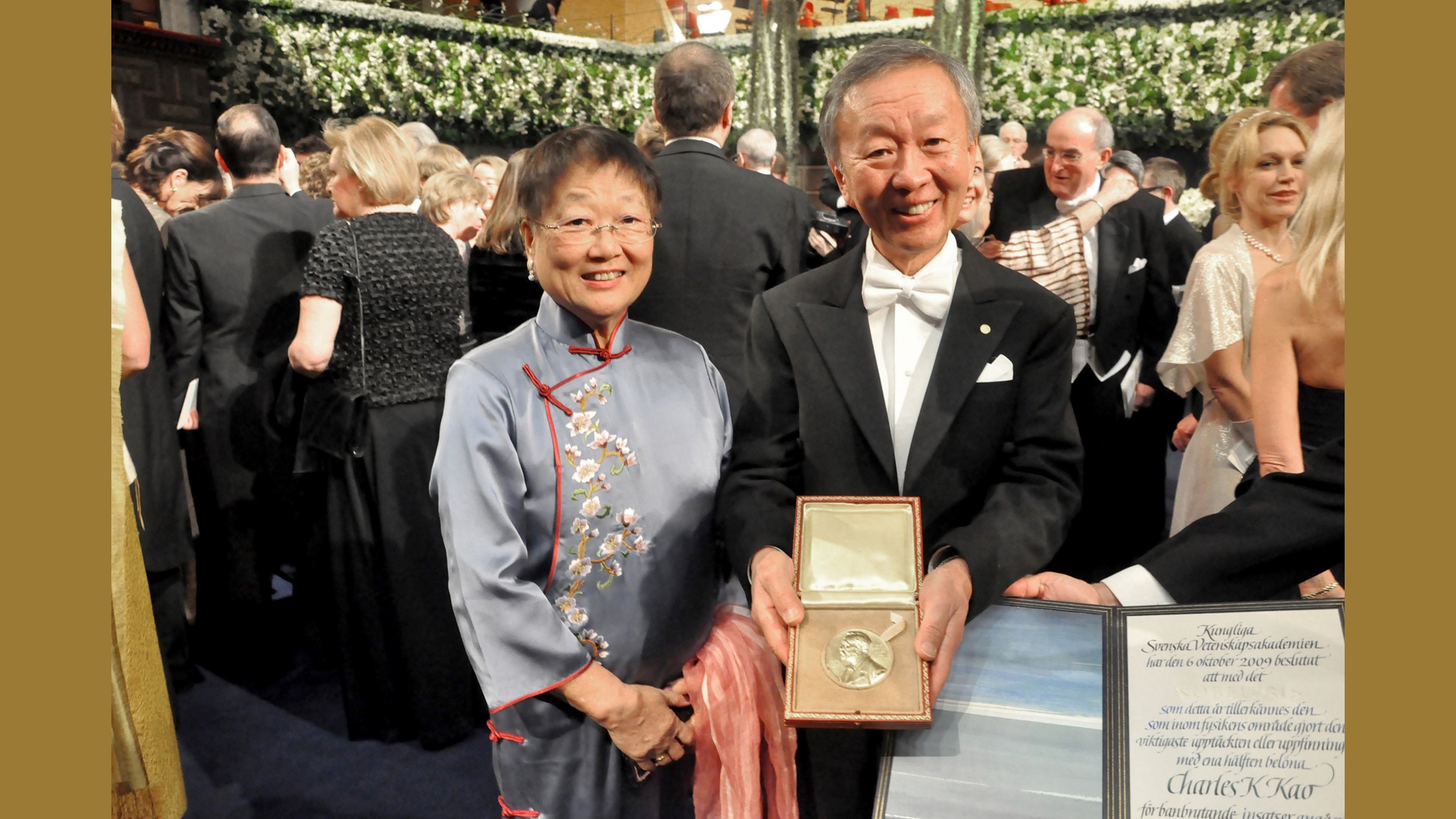

Crowned as the “Father of Fibre Optics”, “Father of Fibre Optic Communication” and “Godfather of Broadband”, the 2009 Nobel Laureate in Physics, Charles Kuen KAO is generally regarded as one of the most significant and influential contributors to engineering in modern times. His “groundbreaking achievements concerning the transmission of light in fibres for optical communication” was instrumental to the explosive development of the age of the Internet.

Early Life and Education

Charles K KAO was born to a wealthy family in Shanghai in 1933, according to the autobiographical sketch published by the Nobel Foundation[1] . His father, KAO Chun-Hsiang, studied law at the University of Michigan in the United States of America and served as a judge in China, and his grandfather, KAO Hsieh, was a Confucian scholar involved in a movement to bring down the Qing dynasty during the 1911 Chinese Revolution.

Since KAO was a child, he had been a science buff and his parents regarded him as a "naughty boy" when he experimented with various chemicals. KAO mentioned in his oral history recording conducted in 2004[2] , “I was playing with chemicals, long before I was really old enough to play with those things, so I got to know things like if you put an oxidation agent and mix it with something that is easily inflammable, that if you mix the two, you are going to make a brighter spark, which I did. The actual things that I used were so lethal. I put red phosphorus powder and mixed it with potassium chlorate, which is an oxidation agent, and we’d touch it and it would go ‘Phooom!’ and explode. For a young boy to be playing with these things is really bad! I actually wrote about this. I made mud balls and put water with those two ingredients in the center and let it dry, and when you’d throw it, it explodes.” The recollection of his childhood shenanigan perhaps was a sign of Kao’s immense curiosity and inquisitiveness.

According to A Time and A Tide: Charles K. Kao ─ A Memoir, his family moved to Hong Kong in 1948 when he was a teenager, before the civil war front approaching Shanghai, and he completed his secondary education at St Joseph's College in 1952. He managed to receive almost straight A’s in the school matriculation examination, which qualified him to apply for the admission to the University of Hong Kong. Yet, the University was still in some disarray after the war and not all faculties were functioning. He then went to London, the United Kingdom to complete his A-levels and obtained a Bachelor of Electrical Engineering degree at Woolwich Polytechnic[3], now known as the University of Greenwich. He was also conferred the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Electrical Engineering by the University College, London University in 1965.

“I like electrical engineering because of its interesting and attractive nature. You will get a lot of satisfaction in the learning process and stimulate your personal creative thinking. In the 1960s, there were not many people doing research and I did research to satisfy my needs. I think engineering is a very interesting field. Engineers are different from ‘scholars’ in that we do research to solve problems encountered in life and make various technological products. Engineering and social development are complementary to each other, making the technology engineers studied more challenging and interesting. The biggest attraction of being an engineer is that he / she is a ‘creator’ who can synthesise past experience to create something that has practical uses for the society. Engineers’ rooms for creativity are endless as there are still lots of things in this world that we should explore and improve. If you like to create and delve into things that are useful to the society, engineering can definitely fulfill your expectation,” said KAO in an interview[4].

Ideas Do Not Always Come as a Sudden Flash

After graduation, KAO joined the Standard Telephones & Cables (STC), a British subsidiary of International Telephone & Telegraph Co (ITT) in United Kingdom. Working there in the 1960s, KAO and his colleagues conducted research that led them to discovering the use of fibre optic cables as a fast and effective medium for telecommunication. They also outlined the cables’ potential capacity for transmitting information — one that was far superior to that of copper wires or radio waves.

Starting as early as the 1950s, traditional radio transmission could no longer meet people's increasing expectations on new telecommunication services. At that time, methods for reducing the loss in signal transmission had mushroomed, but KAO, who was still studying for his PhD, put forward a new idea of using geometric optics and wave theory to reach a deeper understanding of “waveguide” problem. In the early 1960s, optical lasers were in their infancy, performing much below the needed specifications for industrial use and as such the optical systems did not seem to be a realistic option. KAO had already seen the potential of laser and questioned: “How can we dismiss the laser so readily? Optical communication is too good to be left on the theoretical shelf.”[5]

Only two organisations in the world were looking into the transmission component of optical communication at that time, while many others were working on solid-state and semiconductor lasers. Although lasers emit coherent radiation at optical frequencies, using such radiation for communication appeared to be very difficult, if not impossible. Many formidable challenges had to be overcome before optical communication could fulfill its promises.

One of the challenges was about the severe attenuation of light in transparent material – glass. Because of the excessively high signal loss caused by light scattering, glass fiber was widely thought to be unsuitable as a long-distance information conductor and the light passing through a rod of glass simply fades to nothing after a few feet.

Yet, KAO did not think that was a problem that could not be resolved and he began to explore the correlation between light and glass. He found that the optical loss of the transparent material was mainly due to three mechanisms: (a) intrinsic absorption of the material structure itself, which determines the wavelength of the transparency regions, (b) extrinsic loss due to impurity ions left in the material, and (c) the Rayleigh loss due to the scattering of photons by the structural non-uniformity of the material.

KAO realised that, by carefully purifying the glass, bundles of thin fibres could be manufactured and capable of carrying huge amount of information over long distances with minimal signal attenuation. However, at the time, fibre optic communication was only a theory which deemed technologically not feasible. No one believed that there would be impurity-free glass in the world that the transmission of light waves would not be attenuated by such impurities. Despite having to face many doubts and criticisms, KAO remained resolute in his scientific beliefs and continued to lead the group to further improve the experimental results in the ensuing years. KAO often came home late and his wife, Gwen, once complained about it but KAO replied, “please don’t be so mad. It is very exciting what we are doing; it will shake the world one day!”

In the landmark paper on fibre optics in 1966, “Dielectric-Fibre Surface Waveguides for Optical Frequencies”[6] , Dr KAO and Dr George HOCKHAM noted in their conclusion that “a fibre of glassy material” and certain dimensions “represents a possible practical optical waveguide with important potential as a new form of communication medium”, breaking the general belief in the early days that glass fibres were only good for short distance transmission. The theory that they pioneered still underpins the approach behind today’s fibre optic communications.

In 1981, the first fibre optic communication system was developed for commercial use. Fibre optics replaced the traditional copper wire, bringing a breakthrough in communication technology. KAO did not apply for a patent for fibre optic technology, but opened up the technology so that fibre optic communication and the internet can be popularised for the benefit of mankind. KAO once mentioned in an interview, “I am ordinary. I am just doing what a scientist should do when I am conducting experiments on optical fibres.”

“People asked me if the idea came as a sudden flash, eureka! I had been working since graduation on microwave transmissions. The theories and limitations were grounded into my brain. I knew we needed much more bandwidth and thoughts of how it could be done were constantly in my mind,” KAO mentioned in his autobiography[7].

In addition to the 2009 Nobel Prize in Physics shared with Canadian physicist Willard S BOYLE and American scientist George E SMITH, the inventors of the charge-coupled device used to convert optical information to an electrical signal, KAO also received the Alexander Graham Bell Medal and the Marconi Medal in 1985 and the Faraday Medal in 1989. He was elected as Fellow of The Royal Academy of Engineering of the United Kingdom in 1989, Fellow of the National Academy of Engineering of the United States in 1990, Foreign Member of the Chinese Academy of Science in 1996, and also Fellow of The Royal Society of the United Kingdom in 1997, as well as honorary degrees from universities around the world.

A Giant in the Academic World in Hong Kong

Besides the tremendous contributions the Chinese-born physicist has contributed to the world by bringing revolutionary change to modern communication technology, KAO is also remembered in Hong Kong as a dedicated educator, having served as the Vice-Chancellor of CUHK, through a period of expansion and advancement in research standards in Hong Kong, from 1987-1996.

A deep grasp of basic physics is required for good engineering, as is the capacity to appraise the impact of engineering achievements on society. Before he served as the Vice-Chancellor, he, as an advocate for engineering research and education, had spearheaded the establishment of the Department of Electronics (later the Department of Electronic Engineering), which exemplified those values, at CUHK and served as its founding chairman and Chair Professor. In his four years as Head of the Department of Electronics from 1970 to 1974, he laid the foundation for its programmes and later appointed as the first Professor of Electronics. For such short period of time, he had already made significant contributions to the university and considerably strengthened the scientific research environment there.

In 1987, KAO returned to CUHK to serve as Vice-Chancellor and President. During his tenure, he implemented a flexible credit system, revamped the undergraduate curriculum and propelled CUHK to the forefront of world-class research universities, raising the bar for all research universities in Hong Kong. KAO also founded the Faculty of Engineering, along with the Department of Information Engineering, managed to gather a group of talented researchers on the said field. The Faculty of Engineering was established when communication technologies was one of its core areas of strength. Those were the years that the higher education sector in Hong Kong faced massive expansion and called for improvements in quality. Yet, KAO remained the calm scholar with his eyes firmly set on long-term academic development.

Under his leadership, new undergraduate programmes, including Japanese studies, law, primary education, physical education and sports science, architecture, nursing, pharmacy, and information engineering, were introduced. New research institutes, such as Hong Kong Institute of Biotechnology, AsiaPacific Institute of Business, Hong Kong Institute of Asia-Pacific Studies, Hong Kong Cancer Institute, Research Institute for the Humanities, Hong Kong Institute of Educational Research, and Institute of Mathematical Sciences, were also established.

KAO recognised the expanding and potential of biotechnology and the internet early on, and he established research projects in both fields. Being an early proponent of ecologically aware engineering, he published a paper on the subject in 1972. The strong collaborations he forged among academic, industry, and government players created a paradigm for research institutions in Hong Kong, and eventually for the Mainland and also Southeast Asian nations. He retired in 1996 from vice-chancellorship and served as a visiting professor at different institutions and in various honorary positions thereafter.

“Professor KAO was a brilliant scholar and visionary leader in higher education. As the third Vice-Chancellor, he spearheaded the advancement of CUHK in its formative years, laying down a fertile ground for the growth of talents, and made remarkable achievements during his tenure,” said Professor Rocky TUAN, current Vice-Chancellor and President of CUHK[8].

Battler of Alzheimer's Disease

KAO was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease in 2004, a devastating disease that leaves patients with memory loss, disorientation, and behavioral problems. He and his wife Gwen founded the Charles K Kao Foundation for Alzheimer's Disease in 2010, which continues to raise public awareness of the disease, encourage cooperation among different parties to work on this disease and support those affected by it in Hong Kong today.

KAO passed away in September 2018. Upon his death, Gwen said in a press statement[9]: “Our Foundation will keep up our work in supporting people with Alzheimer’s disease and their families. We hope you can show solidarity with our Foundation in supporting the last wishes of Professor Kao.”

At home all over the world, Charles KAO remained deeply rooted in Hong Kong, where he returned for extended periods throughout his life and finally making his home at CUHK. He has left his legacy, including the Nobel Prize Medal and Diploma, and various precious medals at CUHK. “My motto is ‘After my passing away, I would have left a mark on the world, like footprints in the sand’," said Kao at the interview he had at CUHK[10] . We believe his impact and contributions to Hong Kong and the world continues long after his passing.

(Special thanks to The Chinese University of Hong Kong for providing part of the information in the article.)

March 2022

References

- The Nobel Prize in Physics 2009. NobelPrize.org. Nobel Media AB 2021. 3 Dec 2021, from https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/2009/kao/biographical/

- Charles Kao. an oral history conducted in 2004 by Robert Colburn, IEEE History Center, Piscataway, NJ, U.S.A. https://ethw.org/Oral-History:Charles_Kao#Education_and_childhood_interest_in_science The IEEE History Center has a collection of more than 800 oral histories in electrical and computer technology which can be accessed via http://ethw.org/Oral-History:List_of_all_Oral_Histories”

- The Nobel Prize in Physics 2009. NobelPrize.org. Nobel Media AB 2021. 3 Dec 2021, from https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/2009/kao/biographical/

- 一點足印 光纖之父 高錕教授專訪. Engage. 5 Jan, 2022, from http://engage.erg.cuhk.edu.hk/issue4/int_1.htm

- Sand from centuries past: Send future voices Fast - Nobel prize. 6 Jan, 2022, from https://www.nobelprize.org/uploads/2018/06/kao_lecture.pdf

- Kao, K. C., & Hockham, G. A. (1966). Dielectric-fibre surface waveguides for optical frequencies. Proceedings of the Institution of Electrical Engineers, 113(7), 1151–1158. https://doi.org/10.1049/piee.1966.0189

- The Nobel Prize in Physics 2009. NobelPrize.org. Nobel Media AB 2021. 3 Dec 2021, from https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/2009/kao/biographical/

- Mourning Professor Sir Charles Kao, former Vice-Chancellor of CUHK and Father of Fibre Optics. The Chinese University of Hong Kong. 3 Dec 2021, from https://www.cpr.cuhk.edu.hk/en/press/mourning-professor-sir-charles-kao-former-vice-chancellor-of-cuhk-and-father-of-fibre-optics/ .

- In memory of Sir Charles K. Kao (1933-2018). The Charles K. Kao Foundation. 3 Dec 2021, from https://www.charleskaofoundation.org/news/detail?id=DDHfBv46JG.

- 一點足印 光纖之父 高錕教授專訪. Engage. 5 Jan, 2022, from http://engage.erg.cuhk.edu.hk/issue4/int_1.htm

- Ing, T. S., Lau, C. D., & Young, K. (2019). Charles K. Kao, 高錕, Nobel Prize in Physics, 2009. In Nobel and Lasker Laureates of Chinese descent: In literature and science (pp. 131–146). World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd.